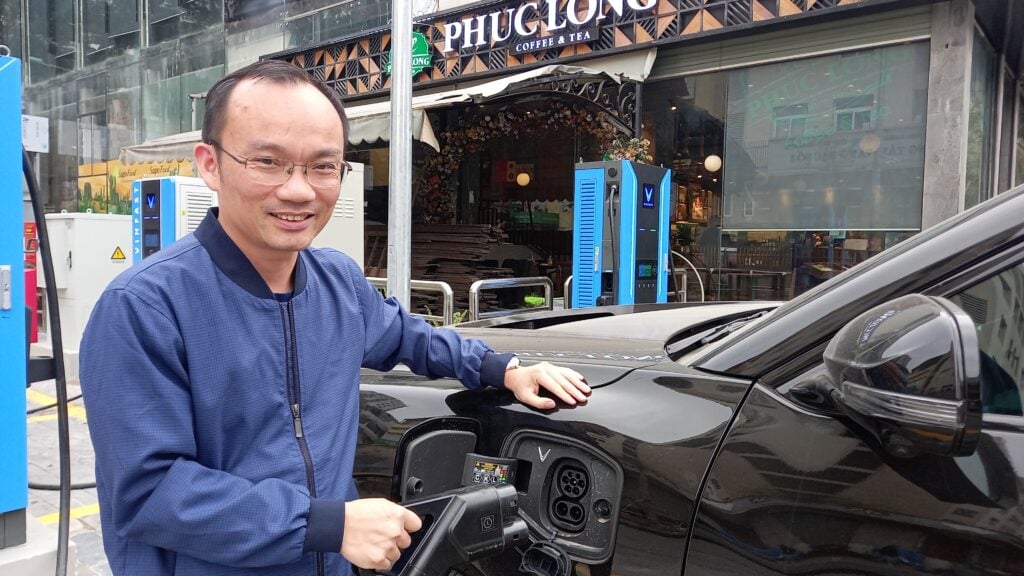

HO CHI MINH CITY, VIET NAM – Tucked away on D3 Street in Thủ Đức City, SolarEV’s charging station is not the typical grid-powered setup. With its signboard hidden behind a massive umbrella, the station could easily be mistaken for a parking lot.

Behind the makeshift tin walls, the station is powered almost entirely by solar panels and a battery energy storage system (BESS) – the first of its kind in the country.

SolarEV started investing in EV charging in 2020 and now runs four solar-powered stations in the south, serving 1,600 users. The company says their humble operation is unlikely to expand anytime soon, citing high costs, fierce competition from grid-powered rivals and murky regulations.

Self-reliant charging stations, meanwhile, are urgently needed as the country pushes the transition to electric vehicles with an already overburdened power grid.

Under Decision 876/QD-TTg issued on July 2022, Viet Nam wants at least 50% of road vehicles to run on renewable energy by 2030, and all buses and taxis to be green by 2050.

The World Bank warned, however, that the country’s latest Power Development Plan (PDP8) overlooked the charging demands of EVs. It estimated the grid would need 3-5% more capacity than now projected between 2030 and 2045 – and up to 15% more by 2050.

“The northern region is already facing power shortages. If EV charging ramps up now, I estimate an additional 15% shortfall,” said Nguyễn Hữu Khoa, Ho Chi Minh City College of Electricity lecturer and SolarEV’s project development director.

Khoa thinks solar-powered charging stations are the quickest and simplest solution to ease the strain.

“If we charge EVs midday when sunlight is abundant, we could cut the national grid load by about 50%,” he estimated.

EV expansion must be matched by the development of charging infrastructures like portals and stations, added Irfan Ul Haq, a lecturer at RMIT University Viet Nam.

A rocky start

SolarEV said their biggest battle was securing initial investment, as solar-powered station required years to break even.

“A charging station of three to five units costs at least VND 1 billion (US$40,000),” said Nguyễn Thị Phưong Dung, SolarEV’s sales director.

“If it is solar powered, the investment rises to at least VND 2–3 billion ($80,000–120,000),” she said.

The most expensive component is the storage system, or BESS. While SolarEV hasn’t disclosed its investment, estimates suggest that a 100kW system like the one on D3 Street could cost up to $60,000, based on a 5kW system priced at $3,000, according to Tuoi Tre News.

Rooftop PV also requires no less than 100 m² per station, adding significantly to the cost.

SolarEV now charges VND 4,000/kWh – half the rate of other grid-powered providers and on par with VinFast’s V-GREEN network, which is willing to operate at a loss.

The company is willing to absorb such short-term losses because they are betting on the long-term profitability of solar power, which is getting cheaper. While SolarEV’s stations still draw from the grid when the PV system and BESS are overwhelmed, they remain primarily solar-powered.

“According to my initial calculation, the ideal payback period for solar-powered stations was three and a half years,” said SolarEV director Khoa.

Tough competition

Since 2024, as V-GREEN swiftly dominated the market, SolarEV was no longer confident on their bet.

In December 2024, Vinfast announced free charging for all EVs until June 30, 2027. SolarEV’s modest 1,600 users, who were mostly VinFast drivers who needed an alternative when V-GREEN stations were overloaded, are now more willing to queue up for free electricity.

“Now, drivers queue at VinFast’s stations instead of coming to us. Our revenue has dropped by about 30%,” Dung told a reporter.

SolarEV now faces a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma. If it expands, it suffers deeper losses. If it doesn’t, EV brands will be even more hesitant to enter the market, leaving them with even fewer users.

“Brands like Suzuki and Honda are cautious about entering Vietnam’s EV market. They want to see if it’s profitable first,” Dung explained. “They would prefer public charging stations like ours, but there are just not that many right now.”

Thịnh Hạnh, the founder of Vcharge, a grid-powered EV charging company, has little hope for the industry. He thinks that any player other than V-GREEN must charge at least 7,000 VND/kWh to survive, and maintain 70% daily usage of their charging stations.

Some are already testing this model, with EVOne pricing as high as VND 9,000/kWh.

But Hạnh argues this approach won’t work until VinFast ends its free charging policy and V-GREEN raises prices.

“Vingroup is keeping prices low to capture the market, so no one else can compete,” he explained. “If you enter now, you’ll fail. It’s better to wait about three years, but if someone wants to take the risk and can afford to hang on, that’s their call.”

Narrow window of opportunity

Viet Nam now boasts about 150,000 EV charging portals – most operated by V-GREEN – putting it ahead of European countries like the Netherlands, France and Germany, and far beyond regional peers like Thailand and Singapore.

But a key challenge remains: uneven distribution.

“Most of the infrastructure is concentrated in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City,” said Ul Haq. “Yet there is a large rural population eager to adopt EVs too. And what about the highways?”

This opens a narrow window for companies like SolarEV to survive without going head-to-head with V-GREEN. In fact, most of SolarEV’s stations are already in provincial areas such as Bình Dương, Lâm Đồng and Phan Thiết – and the company is eyeing highway corridors as its next move.

Government policy is also starting to support this shift. In 2023, the Ministry of Transport’s Circular 09 required rest stops larger than 5,000 m² to dedicate 10% of their parking space to EV charging. The upcoming North-South Expressway will feature 36 rest stops ranging from two to 12 hectares.

“This leaves ample space to install over 1 MW of solar power per station,” said Khoa.

However, regulatory hurdles remain. Current rooftop solar policies apply only to residential rooftops, leaving other infrastructure types excluded.

SolarEV is hesitant to invest in highway charging stations, given the difficulty of finding large-roofed buildings along highways.

“Investors fear that if they set up solar-powered charging stations now and the government mandates their removal two to three years later, they won’t recover their investment in time,” Dung explained.

V-GREEN stations now serve only VinFast vehicles. A government proposal in March 2025 to mandate sharing between charging companies has faced fierce opposition, with concerns about potential foreign market dominance.

Ul Haq argued that the status quo discouraged local EV investors from entering the market, especially in satellite cities and industrial hubs like Bình Dương.

“We don’t really want to go towards a monopoly situation. It kills innovation in the industry,” he said.

Ul Haq suggested that the government set clear standards for land use, installation procedures and safety certifications. Most importantly, they should introduce incentives or subsidies for companies investing in public charging infrastructure, especially solar-powered ones, he said.

“For example, offering loan incentives, affordable land leases, or a guaranteed buyback price for excess solar power could help,” said Thịnh Hạnh.

“Right now, excess power can’t be fed into the grid, and if a charging station is built but not used, it is a waste,” he lamented.

This article was originally published in Vietnamese in Tia Sáng magazine on April 14, 2025.